The fir tree, presents, reindeer, wreaths, the color red, Santa Claus … these associations and traditions are omnipresent at Christmas time. But where do these traditions come from?

Christmas is the celebration of togetherness and contemplation. Some of us are excited to see their family again, spending cozy hours, or — let’s be honest — simply receiving gifts. Others look forward to the Christmas mass in the church or they are dragged there by their family members. Because, as we all know, Christmas celebrates the birth of Jesus Christ and it is often viewed as important to celebrate it appropriately. It is not without reason that churches are not so well attended at any other time of the year. The alleged forgetting and disappearance of the Christian origin in our Christmas traditions is often deplored with in the so-called “War on Christmas” debate. A topic of conversation in the U.S. for some time, it has finally arrived in Germany and is mostly taken up by strongly devout Christians, right-wing circles and concerned angry citizens. They all desperately want the Christianity in Christmas back.

But how did these traditions, whose Christianity is so vehemently sought to be defended, originate? And what do they and our associations with Christmas have to do with Jesus? Was red his favorite color, the fir tree his favorite tree? Or do they have no Christian origin at all? Let’s take a look together.

Christmas as Jesus’ birthday party?

Many of us don’t celebrate Christmas in a particularly religious way, but we still grow up in the knowledge of its Christian origins and meaning. We celebrate Christmas because on this day Jesus was born. Right? Well, not exactly. The Bible, the book that is the foundation of the Christian faith and is supposed to bear witness to Jesus’ life, does not mention a specific day. Instead, it is even extremely unlikely that Jesus was born in winter. According to the Christmas story in Luke 2 1–20, the birth of Jesus was announced to shepherds in a field by an angel. Interestingly, however, it is also very cold in Bethlehem in winter, so it is highly unlikely that shepherds were in a field with their herd at that time. So why do we celebrate it on December 24 and 25, respectively?

Today’s December 25 — before the Gregorian calendar reform in the 16th century, it was December 21 — was already verifiably an ecclesiastical holiday in the first centuries after Christ. However, it was in honor of the birthday of a different god. In ancient Rome, people worshipped, among others, Sol Invictus Mithras, the “invincible sun god.” In the year 247 of our era, the birthday of the sun god, today’s December 25, was proclaimed a state holiday by the emperor of the time. This day was probably dated as the birthday of the Sun God, since it is the day of the winter solstice in ancient calendars, after which the hours of sunlight increase again. The previously pagan cultures, those who believed in no god or several gods, aligned their lives and therefore their religiosity according to the sun, which is why this natural turning point had great importance. The Germanic tribes also celebrated the Midwinter Festival, also called Jul. From December 17 to 24, the Saturnalia also took place, during which excessive celebrations were held.

Pagan cultures aligned their religiosity according to the sun.

Constantine the Great, emperor a few decades later, converted from the pagan worship of SolInvictus to Christianity, still a persecuted religious minority at that time. He became a promoter of the new faith — which eventually became the state religion — and made the birthday of Sol Invictus that of Jesus Christ. In 336, Christmas was celebrated for the first time on record; in the fifth century, representatives of the Church decided that Jesus’ birth should be celebrated on that day forever, since another exact date was missing. In this way, the conversion to Christianity could possibly be made easier for the pagan people, since they did not have to give up their celebrations completely, but officially “only” change the occasion. Most importantly, it was possible to cover up when they did not convert and celebrated the winter solstice on that day instead. This started the practice of the Roman Catholic Church to cover up pagan holidays with “Christian” names and to Christianize them. Even today, many of the Church’s — and our established — holidays fall on originally pagan holidays.

Jul, Christmas, Weihnachten

The german term Weihnachten derives from the Middle High German word wîhen nahten, which roughly means “holy nights.” This name for the holiday is attested only since about the 11th century in Middle German, in other parts of presentday Germany only later. In Middle Low German, the name k e r s t e s m e s s e (C h r i s t mass) initially persisted, its relationship to the English Christmas being obvious. In Scandinavian countries, Christmas is now called Jul, a remnant of the Germanic name for the midwinter festival.

Christmas trees and gift giving are pagan

The Germanic peoples and the people of ancient Rome hung fir branches to worship their gods and decorated them with red berries. A green branch despite the winter is a sign of life. The worship of evergreen trees is also known from other parts of the world, and these customs were adapted and evolved until Christmas trees were first seen in Alsace in Germany in the 16th century. Until about 200 years ago, they mainly decorated public places, as they were rare in Central Europe and very expensive. The tradition of families decorating their living rooms with their own fir trees developed only with the first fir tree breeding companies, which made them affordable and more popular. The pagan origin and connection to the worship of various gods is also recognized by the Catholic Church. Until about 150 years ago, Christmas trees were banned in churches and still are in some churches at personal preference. Also, making wreaths and giving gifts to each other were already pagan customs during the Saturnalia festival and are not in tradition with the gifts of the biblical three holy kings, as is often assumed.

Not only was the day of the winter solstice for Christmas adapted and Christianized, but so were the traditions and customs of the original celebrations. These were too deeply rooted in social practices to disappear with the renaming and Christianization. We still find pagan traditions in other Christian holidays as well, such as Easter, which officially celebrates Jesus’ resurrection, but whose practices were adopted from pagan spring festivals.

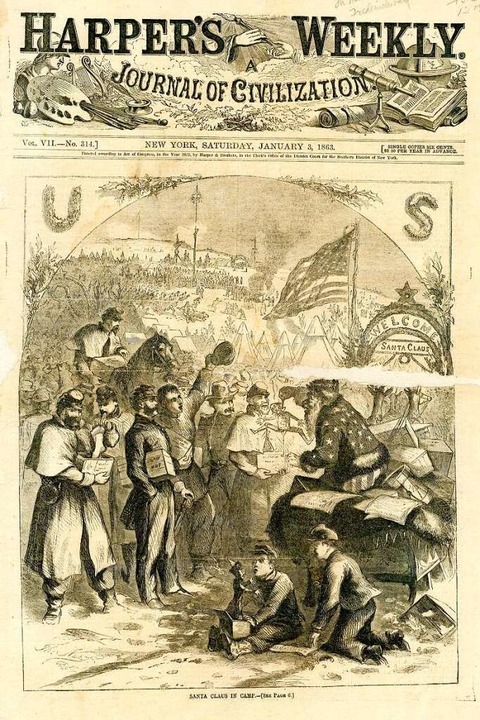

Coca Cola did not invent Santa Claus — but made him famous

Our findings so far probably mean bad news for all the people who are indignant about a “deChristianization” of Christmas. But there is good news, too: after all, Santa Claus — the Christmas mascot par excellence — has a Christian origin, namely in Saint Nicholas, who lived in what is now Turkey in the 4th century. He was considered extremely generous and liked to give gifts. The early church adapted this and officially associated giftgiving with Christmas. Gods or similar are also known from other countries, even before the time of Christ, who are either accompanied by a deer, have a white long beard or, like Sol Invictus, had a pointed cap. St. Nicholas became Santa Claus over the centuries as a result of the mixing of a wide variety of conceptions. In some areas, the Christ Child is still the gift bearer, an invention of Martin Luther, who wanted to break with the Catholic worship of St. Nicholas. However, the idea of Santa Claus largely overshadows the belief in the Christ Child. Our current image of Santa Claus, which we see in advertising, films and decorations at christmas time, was shaped by Thomas Nast’s illustrations. He was a German caricaturist who lived in the U.S. and drew Santa Claus for Harper’s Weekly magazine as early as 1862, along with his now definitive characteristics. His Santa Claus also served as an ambassador in political cartoons, for example, he visited the Northern states during the US Civil War or threatened congressmen with gift withdrawal if they did not advance reforms. Illustrator Haddon Sundblom took up Nast’s interpretation for a 1931 advertisement for CocaCola, which would popularize and famous Santa’s appearance worldwide.

Our traditions are consumer-produced

Just like the establishment of the Christmas tree, most of the other traditions that define Christmas for many have no Christian origin or religious reference, but are brought on by social changes and produced by consumption. The first advent wreaths and advent calendars were not established until the 19th century as a way to shorten the time spent waiting for Christmas — and presents — for the children. Spending time with family and loved ones at Christmas is not an old tradition, either. In the past, Christmas was celebrated in public with markets and nativity plays. Christmas did not move into the immediate family circle until public festivities were partially banned around the 18th century during the Age of Enlightenment because of superstition, and at the same time the importance of the middleclass family increased.

Christmas was never Christian

Christmas, as we know and celebrate it today, has no connection to Jesus Christ or other Christian content in its origins. Instead, our beloved traditions are either born out of consumption or adaptations of pagan holidays and their traditions. This is also the reason why very faithful or churchoriented Christians partly refuse to celebrate Christmas. Christmas in its current form is influenced by traditions from various parts of the world and has always been a social spectacle, just as we celebrate it today.

Text and translation: Joya Hanisch

Illustration Harper’s Weekly: Thomas Nast (commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Santa_Claus_1863_Harpers.png)