A historical search for traces of how St. Nicholas became Father Christmas and how this development shapes our modern idea of Christmas.

“Little dolls, tin soldiers or a rocking horse? Whatever you wish for” is what the 19th century children’s song ‘What does Father Christmas bring?’ suggests. Nowadays it is impossible to imagine the variety of wish lists all across the globe. Gifting traditions based on the celebration of Jesus Christ’s birth have developed all the way from Norway to Egypt, Peru to Singapore. These countries may have different bonds with Christianity, however, one prominent symbol of modern Christmas culture unites them all: the round-bellied old man wearing a red coat, accompanied by reindeer and a large sack, cheerfully smiling broadly. Children love him for his limitless kindness, even if the thought of the punishing rod may seem like it is dragging out the waiting period preceding the distribution of the Christmas presents. Hoping to unwrap the newest smartphone, despite all the little sins of this year, barely any child in this western world is disappointed by Father Christmas. No wonder the number of churchgoers on Christmas Eve is declining, considering all this mercy. The story of Father Christmas also reflects the development of capitalistic postmodernism.

I come from Antalya

It all started long ago in the Eastern Roman Empire, more specifically within the region today known as Turkey. Constantine the Great was the first Roman emperor who converted to Christianity in 312. A few years after, possibly in early December, a man nowadays regarded as the most well-known saint of the Catholic Church died: Saint Nicholas of Myra. Many legends tell of his life. They include resurrecting the dead, calming sea storms and averting famine. One night he gives sacks of gold to three virgins who were almost pushed into prostitution due to their families’ poverty — a first indication of the origins of gifting at Christmas. In his burial church in Patara (today: Demre), picturesquely located in the popular holiday region of Antalya, the mortal remains were stored until the 11th century. When the Seljuks conquered Anatolia from the east, the Byzantine Empire also pushed back Christian influence in the region. Alarmed Italian sailors brought the relics of their patron saint across the Mediterranean to Bari, where they are still kept in a basilica today. French nuns presumably first started putting small gifts into hung woollen socks for children on the eve of his memorial day, 6th of December, in the 12th century.

The rod is calculated

Martin Luther himself is credited with placing the gift-giving tradition of St. Nicholas on Christmas Day in the wake of the Reformation. Luther discredited the worship of Catholic saints as an apostasy. Intercession should only come from Christ himself and only the Christ Child should bring the gifts. Even today, ironically in many Catholic regions of Europe, the angelic child figure plays an important role in the giving of presents. Nevertheless, in the centuries that followed, the symbol of Father Christmas spread across the globe. In Russia, Father Frost came accompanied by the Snow Maiden, in the Netherlands by Sinterklaas, who has retained links to his historical origins through Christian symbolism to this day. In the 19th century, greeting cards were made in Thuringia, with modern red and white Santas as the motif. His attributes: Cheerfulness and goodness, but also punitive severity, in the form of a wooden rod, sometimes carried by his servant Ruprecht. Thus, the educational ideals of European modernity gradually stripped Christmas of its religious foundations. Father Christmas, distanced from the ascetic, Bible-believing and serious-looking St. Nicholas, no longer cared about the afterlife, but executed his judgement on the deeds of children every year in the living rooms of Central Europe.

Taste the Feeling

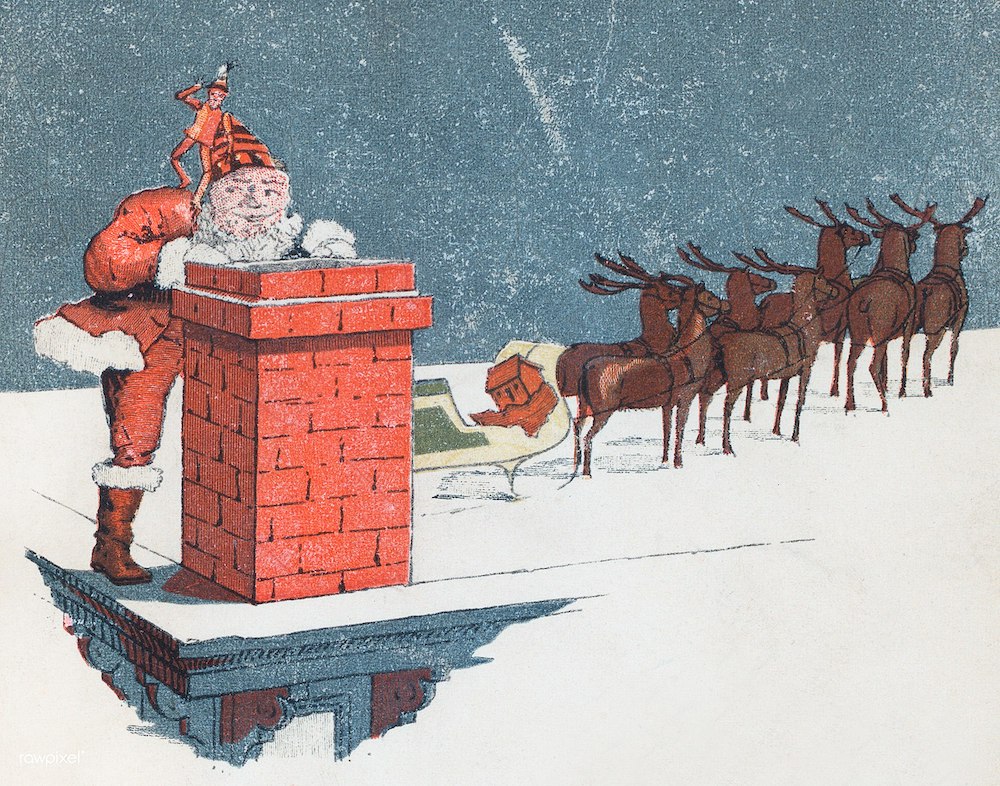

With the rise of America as a global economic power, Father Christmas also underwent a final and significant transformation that continues to shape our attitudes towards Christmas to this day. In the money rush of the 1920s, shrewd marketing strategists looked for new ways to boost sales of a cocaine-infused soft drink that had fallen during the winter months. They hired cartoonist H. Sundblom to illustrate the association between Father Christmas and Coca-Cola, which he managed to do very well, especially because of the colour analogies. Thanks to his artistic skills, the rumour that the company invented Father Christmas has persisted until now. After decades of global advertising campaigns, almost every child in the world wants to receive presents from the pot-bellied X‑mascot. In addition, in times of digital consumption, it only takes two clicks for a letter to arrive at the Christmas post office at the North Pole. Meanwhile, the helpers in the Christmas factories are being sent to load the reindeer sleighs faster. There are still so many eagerly waiting children whose wishes need to be fulfilled. No one likes children being sad at Christmas. Their craving for the latest entertainment technology is fed by the mixture of advertisements and the materialistic need for wealth of the parents who communicate between the almighty Father Christmas and them. By making themselves his assistants, they reproduce the myth of an old white man watching over the temple of consumption.

Who still believes in Father Christmas?

When we collectively associate the Christmas season with exuberant consumption, we play into the cards of big corporations and pay homage to Father Christmas, their representative. Even if his smile has often been hidden in recent years for reasons of infection control, during the Advent season his presence is omnipresent in public spaces. And even if there is something like thoughtfulness in the living rooms, when we are sitting together with our fragile families in candlelight and are eager to see how much love is waiting under the electric Christmas tree, he is there in the form of gift and chocolate wrapping, in poems, songs and proverbs. He is the manifestation of the brief moment of happiness of material need satisfaction, someone who is there waiting for one in the distance. Because of his almost limitless knowledge of our desires and his ability to turn them in concrete actions, he is worshipped like a prophet, and not only by children. But due to the deprivations of recent years, a change seems to be gradually taking place. In order to avoid both the annual gift stress and a viral illness, a Father Christmas is requested less frequently by shops. Besides, the Christmas business is increasingly shifting to the internet. The postmen are so rushed and underpaid that any longing for the exciting Christmas mail creates a bitter aftertaste. With all the overabundance of consumer goods, children seem to be becoming more indifferent to their gifts. They also realise that there is no real festive spirit if only half the family is allowed to be there and the warmth otherwise created is missing. But this gift cannot be unwrapped and held in one’s hands. It is a different form of Christmas, free, selfless and shapeless. Strengthening interpersonal bonds without making use of material aids requires motivation and initiative, but is more sustainable in return. Perhaps the current calls for frugality are a chance to rediscover comfort within the family.

Text: Lennart Kreuzfeld

Translation: Carla Graham

Pictures: Lennart Kreuzfeld, PxHere

Illustrationen: William Lionnel Wyllie (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0; commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Father_ Christmas_1887_RMG_PV2502.jpg; Credit: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Caird Collection; cropped), unbekannt (commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:1914_Santa_Claus.jpg), unbekannt/Rawpixel (CC BY-SA 4.0, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vintage_ Christmas_illustration_digitally_ enhanced_by_rawpixel-com‑8.jpg)