The Matilda effect describes the systematic discrimination of female scientists. Its name stems from Matilda Joslyn Gage, a feminist and sociologist, who opposed the widespread sentiment that women were not suitable for scientific work. This article will highlight some of the extraordinary scientific achievements and contributions made by women in science.

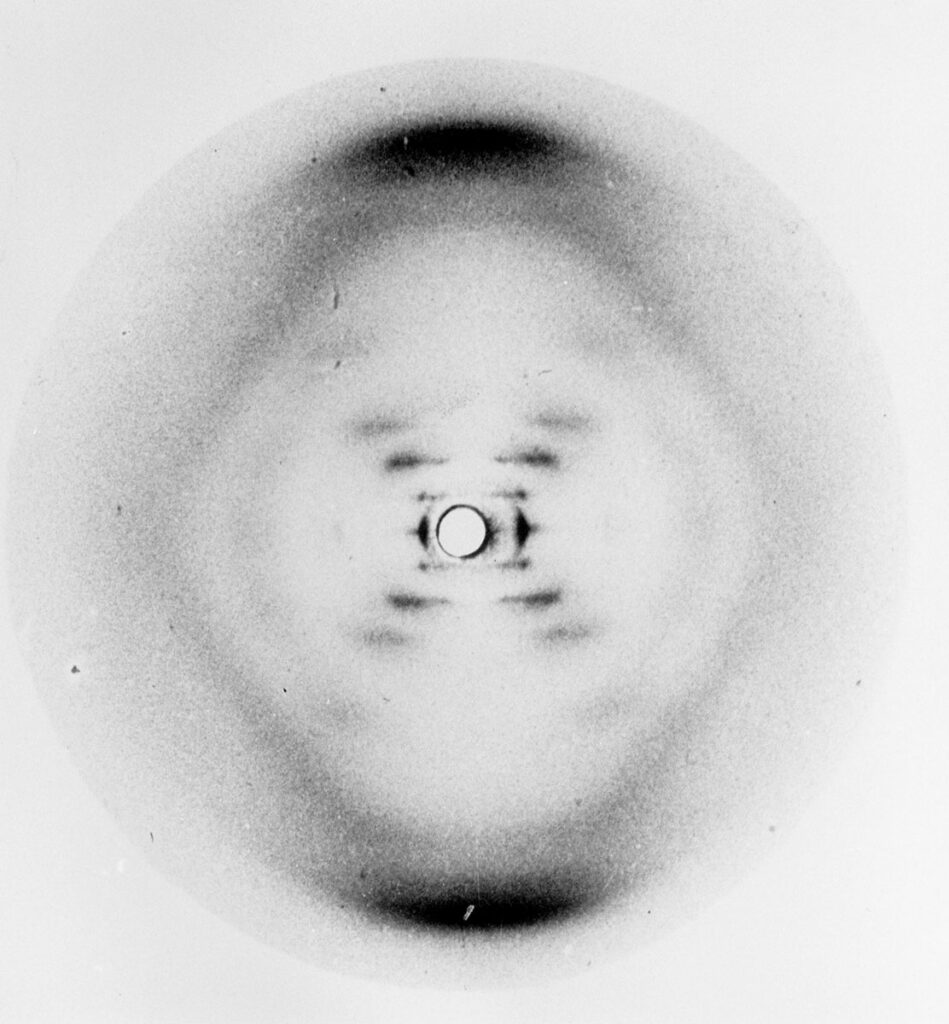

The work of biochemist Rosalind Franklin represents one of the best examples for the Matilda effect. She focused her studies at the London King’s College on decoding DNA with the help of roentgen radiation. Franklin discovers two types of DNA molecules, manages to take high-quality pictures, and discovers the existence of a helix structure.

KDBP/1/1/867, King’s College London Archives

Meanwhile, the two (male) scientists Watson and Crick create a first faulty DNA model after attending one of Franklin’s presentations. Maurice Wilkins, vice head of the laboratory in which Franklin was working, secretly copied her documents and passed those to them. Among them was the famous Photo 51 — the evidence proving the existence of the double helix structure. Additionally, the report of her findings was also passed to Watson and Crick without her knowledge by a member of the assessment committee, which gave them the necessary data for their model. They published their work in the same journal as Franklin’s report, which was interpreted as verification. Four years after Franklin’s death, Watson and Crick received a Nobel Prize for this discovery. Neither she nor her contributions find any acknowledgment in their acceptance speech. Years later Watson, in his book “The Double Helix”, admitted to how much the team profited off of her work but rather than talking about her work, he commented on her appearance:

“By choice she did not emphasize her feminine qualities. Though her features were strong, she was not unattractive and might have been quite stunning had she taken even a mild interest in clothes. This she did not.”

One small step for a human …

As the only female student taking Analytical Geometry, Katherine Johnson graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Mathematics and French at the age of 18. She got the opportunity to be one of the three first Black people who were allowed to study at an American public university, and is the third Afro-American person to obtain a doctorate degree in Mathematics. Later, Johnson starts working for the NACA, the predecessor of NASA. During the segregation, the “renting out” of Black mathematicians to other departments was common practice. She is the first to insist on being allowed into the briefings of the department of aviation research. Johnson is the only woman who manages to transition to another department, as her expertise quickly made her indispensable. Prompted by a deficit in textbooks on space travel, she and a male college wrote a scientific paper and she consequently becomes the first woman to be credited as a co-author in the department. That paper serves as the foundation for NASA’s first manned space travel and enabled the first complete orbiting of Earth by an American astronaut among other things. Furthermore, Johnson calculated the correct flight path and orbit for the Apollo 11 mission, developed a manual navigation system and made calculations essential for the return of the Apollo 13 back to earth. Besides countless awards from NASA, Johnson receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom from then-President Obama in 2015, one of the highest civil honours in the USA.

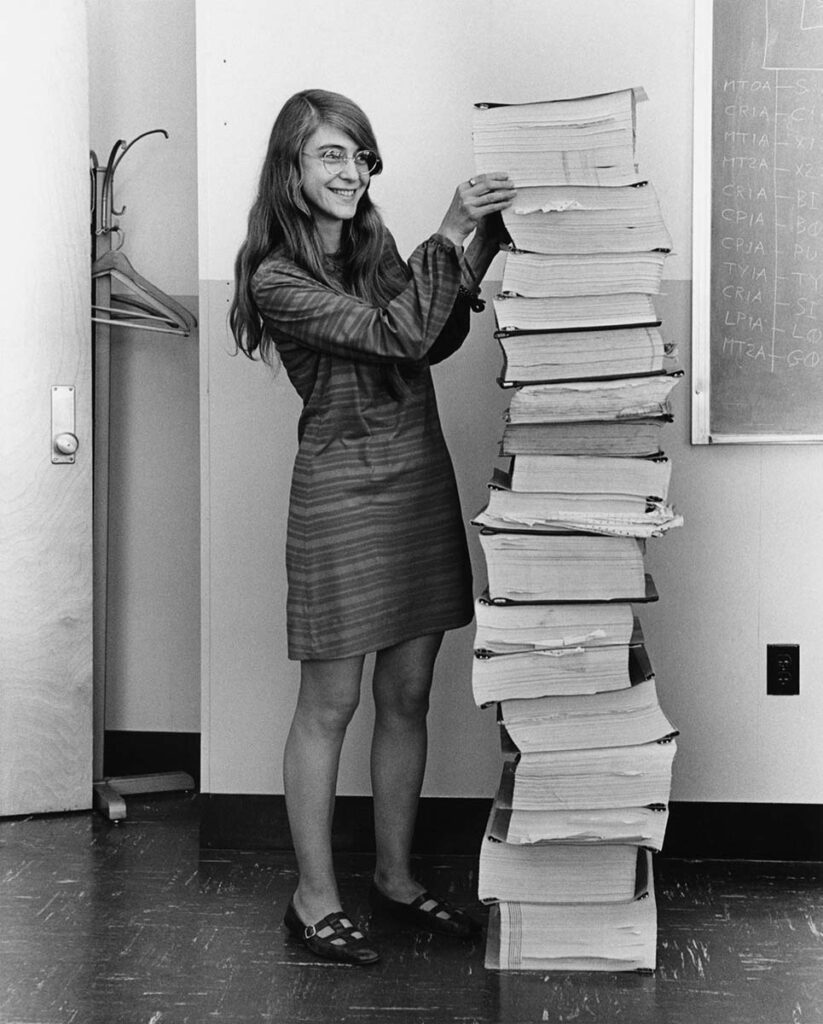

… one giant leap for humanity

When thinking of Apollo 11 and the moon landing of July 20 1969, most people think of the three male crew members — Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins. Few are aware of the role that Margaret Hamilton played. The mathematician is considered to be the first software engineer and was responsible for the development of the flight software. This was essential for the navigation to the moon and back, as well as the successful landing. She developed concepts for asynchronous software, which enabled the execution of several operations at once without blocking others, and methods for a priority guided task execution. Hamilton relied on the harmonised interaction of hardware, software, and humans, which allows the pilot to take control at any time. Occasionally, the working mother brought her daughter to MIT. When she accidentally pushed a button causing a system crash, Hamilton advocated for the installation of protective devices and backup systems. Contrary to the popular belief that astronauts do not make mistakes, the same mistake happened during the Apollo 8 mission, which was fixed in very little time by her team. The landing of the lunar module during Apollo 11 was interrupted by an error message and close to cancellation. But Hamilton’s software was able to handle the additional amount of data caused by the unplanned activation of a radar system, thanks to her prioritisation system. After the conclusion of the Apollo program, she founded her own software company and received several awards; among them was the highly endowed Exceptional Space Act Award, the highest award ever given by NASA, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

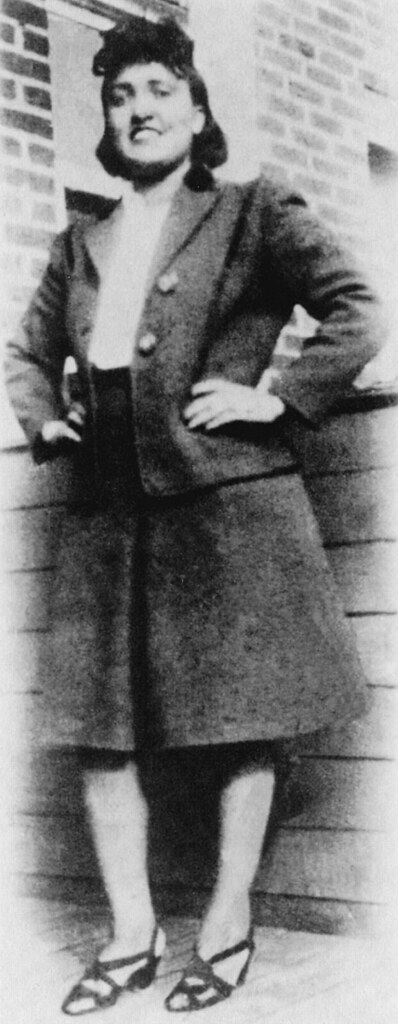

Immortal cells

Cell and tissue donations are indispensable for science. HeLa cells are of particular medical relevance. They are used to research cancer drugs, developing vaccines, and in student education, among other things, and are particularly well known for their unlimited capacity of cell division. Although they are one of the first and most frequently used cell lines in biomedical research, their origin remained a mystery for a long time. HeLa cells originate from involuntary tissue removal. They were taken from the young African-American woman and mother Henrietta Lacks after she lost her battle against a particularly aggressive form of cervical cancer, just eight months after she was diagnosed. This happens without her knowledge or consent. Her family also does not find out about the involuntary tissue removal for almost 20 years. The cells were irradiated and genetically manipulated — her cell’s success story begins. Today, an estimated 50 million tonnes of HeLa cells are still ‘alive’ in laboratories around the world and are still used for basic research. Henrietta Lack’s cells have reportedly been used in more than 70,000 medical studies.

Sit and watch in silence?

For the Dutch micro-biologist Elisabeth Bik, the answer is definitely “no”. In her work she concentrates on bacterial genetics and microbiome research, Bik got famous for uncovering scientific malpractice relating to image manipulation in scientific publications. The whistle blower reviewed over twenty thousand papers in different journals and discovered that nearly 1 out 25 papers shows manipulated western blots. After letters to researchers and editors were left unanswered, she and two of her colleagues published a paper on scientific misconduct in 2016 and campaigned to ensure the credibility of scientific research. Her work has contributed to the discovery of falsified or duplicated images in studies on the treatment of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. She shares her research on X and her blog (scienceintegritydigest.com), among other places. In 2024, Bik received the Einstein Foundation’s Institutional Award for her work.

| Blotting In molecular biology, blotting refers to a process for transferring molecules onto a membrane. The Western Blot describes the transfer of proteins onto a carrier membrane, which are detected by subsequent reactions. |

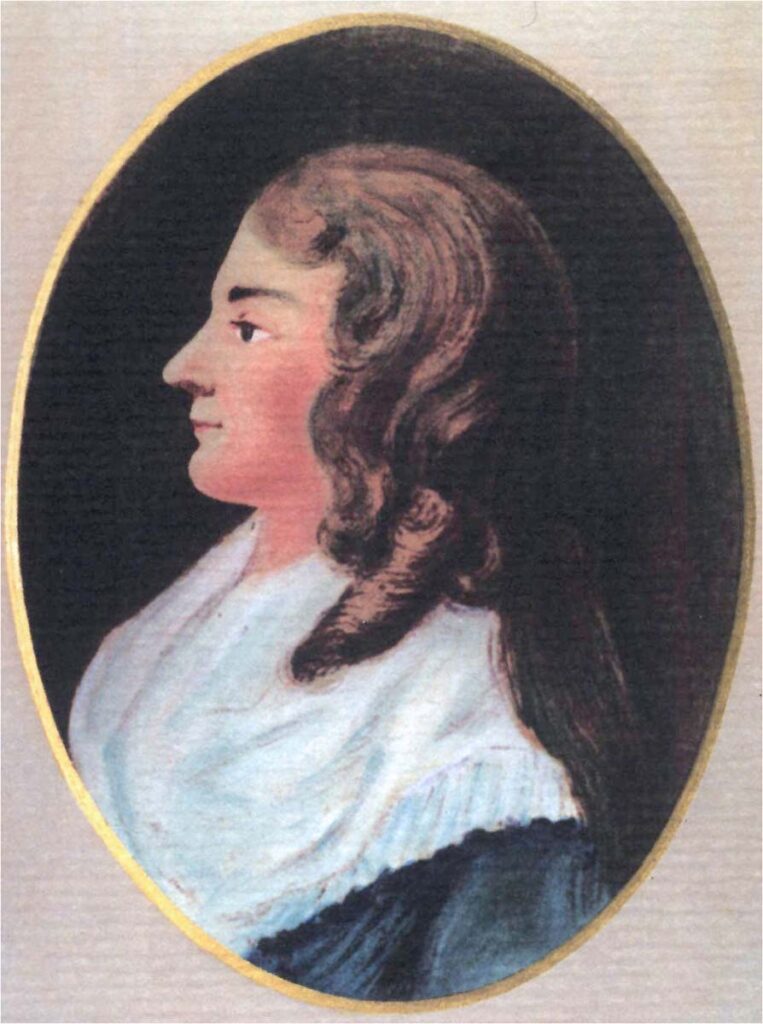

Germany’s first female doctor

As the daughter of a doctor and grammar school teacher, Dorothea Erxleben, born in Quedlinburg in 1715, received the same school education as her younger brothers, which stood in contrast to the social standards of the time. She taught herself most of her knowledge, including Latin, and accompanied her father on medical visits at the age of 16. Although she was denied the opportunity to study medicine, her father allowed her to assist in his practice. In 1740, she asked the new King Frederick II for permission to attend university. Her request was granted and she was enrolled in the University of Halle. However, she was never able to study, as her brother, without whom she would not be able to attend lectures, was drafted into the war. She’s eventually married, had children and continued to work as a doctor in her father’s practice, which she took over after his death in 1747.

As Erxleben did not have a medical degree, male colleagues reported her for medical malpractice after the death of a patient, whereupon she was banned from being a doctor. She protested against the ban and completed her doctorate by submitting her thesis. In 1754, Erxleben became the first woman in Germany to be awarded a medical doctorate. She also criticized the usage of expensive “trend drugs” and with that opposes the general direction of her era’s medical development. In the society of her lifetime, her vita is a tremendous outlier. High School classes for women were first offered in 1893, while entry to German universities was only made possible after legislature passed the Federal Council in 1899.

The histories of these and countless other women show that neither sex, nor origin, nor sexual identity has influence over ones abilities. The problem of ‘invisibilisation’ of women and minorities can be observed not only in the natural sciences, but in almost every field of life. By drawing attention to forgotten and oppressed people and their history, and by recognising their achievements, a reappraisal and a change in the social norm can take place.

Text: Sarah Becker

Translation: Jonne Pietryas