A perpetual flow of texts, pictures, moving pictures. What makes it into the canon of the broad media public?

Media attention can be an important pressurizer in political issues – as well as in the context of the Iranian government’s violent actions against its own population.

Jina (Mahsa) Amini died on September 16, 2022, after she got arrested by the Iranian morality police. Since then, people in Iran take to the streets under the slogan Jin, Jiyan, Azadî (Kurdish version of Zan, Zendegi, Azadî, English translation: Woman, Life, Freedom) – in a country where the slightest resistance against the regime can result in death.

After the tireless spread of information via social media, above all by Iranian citizens and a few journalists, reports about the protests are gradually finding their way to a broader (media) public: The daily prime time news program reports on the ongoing situation in Iran, talk shows are inviting experts, TV hosts Joko Winterscheidt and Klaas Heufer-Umlauf hand over their Instagram channels and the reach that comes with them to the Iranian activists Azam Jangravi and Sarah Ramani; institutions express their solidarity, including the College of Arts Burg Giebichenstein in Halle and the students council of the Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg. There was no public positioning from the rectorate of the MLU, no sign of compassion via Instagram; despite hints and messages from Iranians in Halle and a demonstration at the Universitätsplatz.

Conversations with the Iranian students Hevidar* and Azadeh* show disappointment about the absence of reactions from the environment and the university: attention from here is important – it is important to look, Hevidar says.

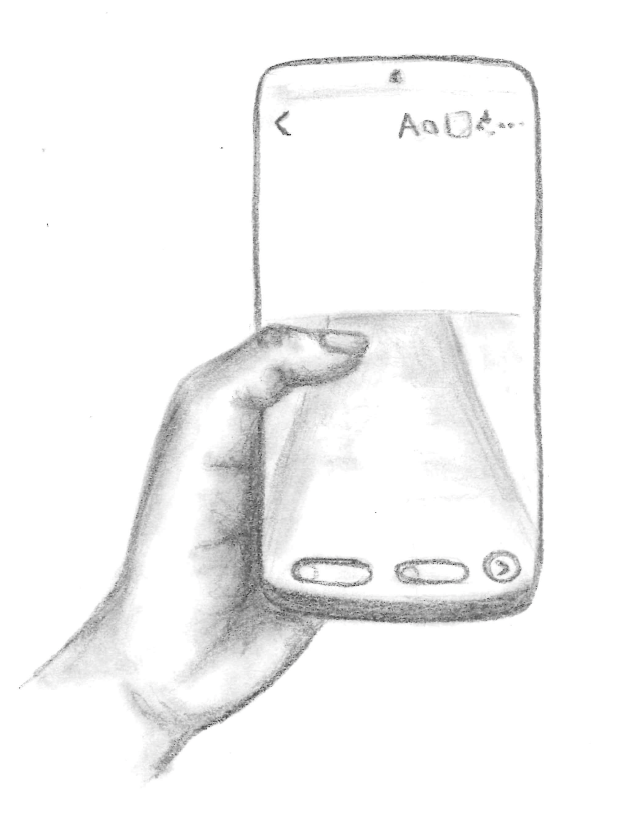

A couple weeks after the beginning of the feminist revolution, both narrate to almost permanently update the news. A normal everyday life is hardly conceivable.

Nothing to lose

Hevidar is studying in Halle and has been living in Germany for four years. It is in the end of November as we speak; the protests have been going on for more than two months at the time of our interview. Hevidar rarely has contact with her family in Iran, no more than two- or three-minutes conversation would be possible without an interrupted internet connection, she narrates.

Already in November 2019 the internet in the Islamic Republic of Iran got cut. Also, in those days the people protested economy and politics, triggered by the announcement of the increase in gasoline prices.

Thereby – hidden from the eyes of the world by the internet shutdown – at least 304 people got killed within four days, according to Amnesty International. During the entire protest period of nearly two weeks, reports claim around 1,500 fatalities – one of them was the cousin of Azadeh.

Azadeh is studying in Halle, too. In September 2022 she visits her family in Iran for the first time after three years. During her stay, Jina Amini dies.

Back in Germany, in conversation she narrates that the demonstrations are about more than the Hijab: They are about the economy, about the whole situation in Iran – the people would not see any future, they could not afford anything, there would be no security.

This also reflects in the words from Natalie Amiri, a German-Iranianan journalist. In her Instagram-Story on December 10/11 she says, originally in German: “The people were deprived of the air to breath; on the one hand because of the desolate economic situation, because of the longstanding sanctions but also because of the mismanagement and corruption, degradation and discrimination through the regime”. According to her, the big difference in comparison to the years before is that the people were not intimidated anymore: “The people have nothing left to lose and face a regime which has everything to lose”.

For freedom

Hevidar says that the mother of one of her classmates was killed – shot with multiple bullets during a protest within the first couple weeks of the feminist revolution. She had been a great woman, a person with a smile, brave and strong; she had always urged her daughter to share her food with her classmates, Hevidar tells.

Hevidar recalls conversations with her father: he is ashamed to still be alive, whereas on the streets kids and adolescents are murdered, he always tells her that revolutions have their costs and they must be willing to give their lives for them so that their kids, their grandchildren and the upcoming generations maybe might one day live freely in this country, Hevidar narrates. “We have to have hope, we just have to keep going”, Hevidar says. According to her, the people are fed up: Why living if daughters, mothers, sisters, brothers got killed by the government?

She has had her headscarf on, wore long trousers and a blouse, over it a coat whose buttons were open when the morality police approached and spoke to her, Hevidar remembers: She should close her coat. A moment of fear, the thought that she could be taken away. She says that her father directly went over to her. Those minutes alone were frightening, Hevidar tells, even though nothing more actually happened.

It is mandatory for women in Iran to wear the Hijab – Jina was taken away, because hers was not fitting properly; even public dancing and singing isn’t allowed for women in the Iranian republic.

Hevidar wishes that trivialising the regime stops, that the government is not accepted as such, that [further] political sanctions are imposed. Even though she knows that changes have to start from within, she thinks that pressure from the outside is useful and good for the revolution.

Middle of march: Azadeh has no more hope, the people are disappointed, have had attached to the situation, she believes. Life goes on, everything became even more expensive and the Instagram channels of her friends in Iran would appear to be nothing has ever happened, she says. However, hardly anyone goes out on the streets with hijab – a picture which get confirmed in social media postings.

03-15-2023, @sepideqoliyan tweets a video. It shows herself, Sepideh Qolian, released from detention after four years and seven months. In addition, she writes in Persian “[…] This time I came out hoping for the freedom of Iran! […]”. With loose hair and a bouquet in her arm she walks on the street between people and calls something in the video. The video gets shared and commented, her calls get translated (with slightly modified wording) several times – her words are directed to Khamenei, the supreme leader of Iran: We pull you down to earth/We bring you under the earth.

03-16-2023, @DuezenTekkal, @Khani2Mina, @NatalieAmiri, … tweet. Sepideh Qolian got arrested again.

“The truth is us”

Since the mid of december, the Instagram channel irandetaineereports publishes information about people who got detained, killed or executed; who have been released on bail or are missing. Posts are still being made, often several times a day. 41, 69, 7. Abstract numbers, which may make one forget that behind every number are people. People with relationships, needs, dreams, pain and hope. The Instagram channel provides insight into some stories, shows faces behind the numbers, gives a short context to the judgement – among others about 41 sentenced to death, 69 in danger of execution and seven executed (State: 11.04.2023). The actual scale of executions goes far beyond this: On the 2nd of March Amnesty International reports 94 people who got put to death by authorities, alone in 2023. Kurds and Baluchis are particularly affected – ethnic minorities in Iran. The executions are based on unfair trials extorting confessions by means of torture. Dieter Karg of Amnesty International demands pressure from the German government.

Middle of April: After Nouruz, the Iranian New Year, everything would have become a little different again; it goes on, protests are in progress, Azadeh narrates. The government would try to state new rules, the morality police should collect all women without Hijab on the streets. The headscarf mandatory is now controlled by surveillance cameras, is reported on social media and in news.

Natalie Amiri writes in an (originally German) Instagram post, dated April 10, 2023: “No matter who am I talking to in #iran, he/she tells me: ‘We will reach our goal…’ It will be a long dangerous road with an incredible number of hurdles […]. The West has no interest in a change of the situation in the region […]. The neighbouring patriarchal Islamic countries have just as little interest in seeing a regime of men fall through the power of women. China and Russia benefit anyway throughout this regime. So, in the end, only the power and will of the people remains.

Social media continues to be the space where a big part of news coverage takes place; where attention is drawn to the ongoing fight of the people and the brutality of the Iranian government; where torture, rapes, poisonings and executions are relentlessly reported.

In Iran, every person with a smartphone in their hand would be a journalist, in which journalist wouldn’t be the right word, Hevidar believes – but a kind of person who reports what exactly is happening on the street: “The truth is us”, she says in our conversation.

Surrounded by numerous news from all over the world priorities are set in media reporting – they must be set. But what stories do we tell, which fights do we see, which human right abuses do we name?

Whether consciously or unconsciously, we value events with our priorities; rate human lives. Especially in crisis and survival situations, media attention becomes a currency that might save lives – but therefore, we have to look. With our interactions, above all on social media, we can still help the Iranian people gain visibility, reach and attention as people in Iran are still fighting against the authoritarian government: For their rights, for their freedom, for their future.

*Names changed by the editors.

Besides the interaction on social media for reach, there is also the possibility to help via Snowflake. Snowflake is a system which enables people from all over the world to access censored content on the internet. For this purpose, users are randomly matched with a Snowflake proxy. This requires Snowflake proxies installed by volunteers from countries with little Internet censorship. More information on how the system works and how to download a Snowflake proxy can be found on the website https://snowflake.torproject.org/ – basically, the download requires nothing more than a laptop or smartphone and a working internet connection.

Text and illustrations: Renja‑A. Dietze